Wind the clock back.

Travel back in your mind to a time long before paved roads and the cars that travel them; before the buildings now preserved in the Yosemite History Center were built in the early 1900s; and before Yosemite was designated as a National Park in 1890. Let’s go back to the edges of the times we know about today – to stories of people who lived here for generations, the people whose ancestors lived here when the ancient sequoias we admire today were still saplings.

Imagine a rich landscape, sparkling, clear rivers filled with sweet Sierra water, and beautiful open meadows teeming with wildlife. Does the scene make you want to stop and stay a while? It certainly seemed that way to the people that lived here then.

One name for this place was Pallachun, meaning “a good place to stop.” And it’s still a good place to linger today, to appreciate all of the quiet and beauty nearby, even though we now call it Wawona.

(The new name was given in 1882 after what is believed to be the Mono Indian name for giant sequoias – Wah Who Nau. It is thought to come from the sound of the hoot of the great horned owl that was the guardian spirit for these ancient trees.)

The Earliest Residents

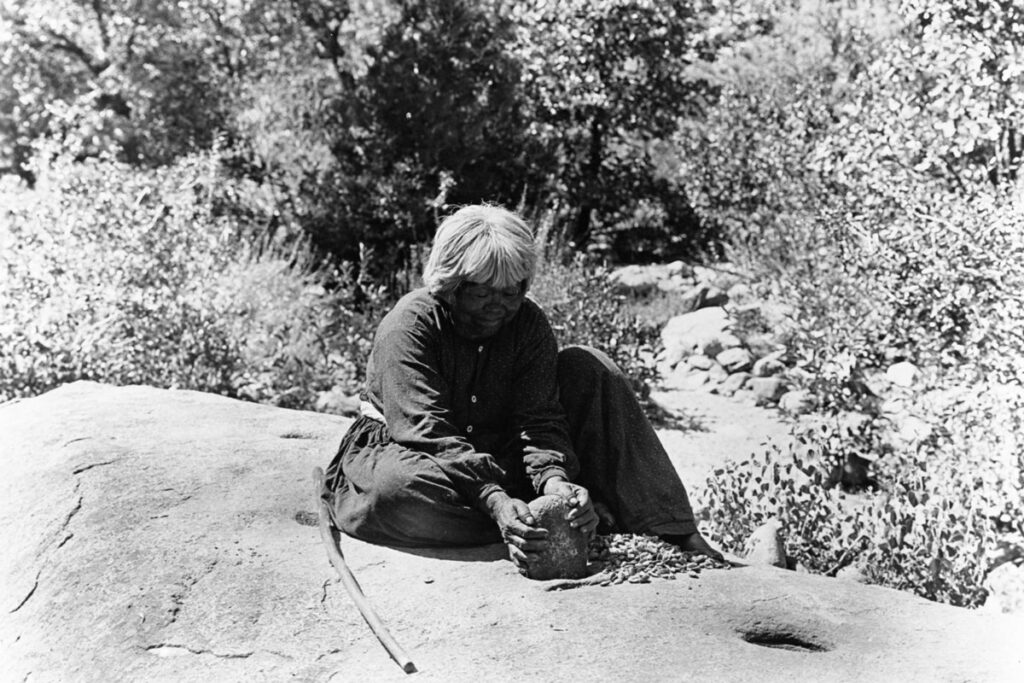

Ta-buce, or Maggie Howard, collecting acorns in Yosemite Valley. Photo taken in 1936.

Archaeological evidence suggests that people lived in the Yosemite area as long as 8000 years ago. In the old Miwuk stories, people were created by Ah-ha’le (Coyote) to have the best characteristics of the animals, and the cleverness of the coyote himself to gather and use the richness of the plants and animals there. Today, we have evidence that these earliest known residents crushed seeds on flat rocks, and hunted using spears and atlatls.

The most current understanding is that by the late 18th century, most of Yosemite was populated by the Southern Miwok people, with some Central Miwok people in the northern reaches of what is now Yosemite National Park.

However, the history of precisely which tribes and sub-tribes lived in Wawona is complex and hard to define. Currently, seven tribes are recognized as having ties to areas inside Yosemite National Park. These include the Bridgeport Indian Colony, Tuolumne Band of Me-wuk Indians, Mono Lake Kootzaduka’a, Bishop Paiute Tribe, Picayune Rancheria of the Chukchansi Indians, and the North Fork Rancheria of Mono Indians of California, as well as the Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation.

Finding Signs of Early Native Civilization Today

Pounding Rocks

Large mortar rocks were used to process foods, like these acorns. When we find these special places, we can imagine people here preparing food for their families.

If you know where to look along the South Fork of the Merced River and along the Wawona Loop Trail along the edges of the meadow, you can find mortar rocks that were used to process food. Look for circular depressions in the tops of boulders, often in a place where a person preparing food would have easy access to water. These places now often provide a good view of a nearby meadow or river.

These were used like we might use a mortar and pestle now, except on a much grander scale. Each pestle weighed from 5 – 12 pounds and could be used to pound a gallon of acorns at a time. The resulting acorn flour would be sifted, and then the coarser pieces pounded again until the fine flour could be rinsed free of the bitter tannins and used to make dough.

If you look carefully, you’ll see many sizes and depths of the mortar holes. Each mortar was designed for a specific use. For example, shallow mortars were better for pounding acorns, while deeper mortars were preferred for preparing manzanita berries.

Arrowheads and Spear Tips

Obsidian knives have been discovered throughout Yosemite, leaving important traces of native culture.

If you look carefully you might also spot obsidian arrowheads and spear points in Wawona and throughout the region. Be sure to leave these where you found them! These important archeological artifacts provide important information about where native people lived and traveled. Removing these artifacts erases an important piece of tribal history.

While the shafts of arrows are made from local mock orange or spicebush shoots, and the feathers came from local birds, you can’t find the obsidian needed for arrows and other tools in this area.

To get these, you would need to get them from the east side of the Sierra.

Obsidian caches found along known trade routes and other archaeological findings demonstrate that the people living in Wawona before the mid-19th century had a robust and well-established network of trade and commerce that extended from beyond the Sierra Nevada mountains to the east and all the way out to the west coast.

In fact, when Stephen Powers travels through the region in 1877, he’s struck by how easy it is to communicate. While there are, of course, many different dialects, often the root remained close enough that many people could communicate effectively. He wrote, “An Indian may start from the upper end of Yosemite and travel with the sun 150 miles… without encountering a new tongue, and on the San Joaquin make himself understood with little difficulty.”

Trade included obsidian from the eastern Sierra to sea shells from the coast, as well as finely crafted baskets with a wide range of uses. In the mid-19th century, the Miwuk were renowned for their brilliantly crafted arrows, made from local plants such as Mock Orange or Spicebush.

Disruption and Devastation in the 19th Century

People built acorn granaries to preserve this important food resource.

It’s hard to pin precise dates on how far back the many generations of people followed the natural rhythms of the year. They followed animal migrations and harvested many plants and mushrooms as they came into season. In late summer or early fall, the people would set fires to promote the growth of plants that were useful to them and clear the ground to make gathering food easier. In the fall, they collected acorns for food and stored them in granaries called “chuckahs”. Dried meat and dried mushrooms were prepared for the long winter months. Some people would move to lower elevations for the winter, returning again in spring.

However, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, their lives changed dramatically. California’s Gold Rush of 1849 brought thousands of non-Indian miners to the region in search of gold and began to “lay claims” to pieces of land. In 1850, volunteer militias like the Mariposa Battalion were formed to “protect” the newcomers by forcing the native residents out.

Thousands of native people were killed or died of starvation following this disruption. By 1910, only 1 in 10 of the original Ahwahneeches (the people who lived in Yosemite Valley) were alive and accounted for.

Many tribes signed treaties with the new government, moving to the Fresno Indian River Reservation as agreed. But like so many similar treaties of the time, these were only honored when it was convenient. Soon enough the reservation was overgrazed by the herds of white cattle ranchers, treaties were ignored, and less than 10 years later, in 1860, the failed Fresno reservation closed. Now landless and without legal status, the people were forced to move again.

Return

As they returned to the area, some found work demonstrating their cultural practices, as well as other jobs in the community. Photo Grace Anchor making manzanita cider as visitors watch.

Having nowhere else to go, many of the people moved back to their traditional homelands. They resettled in Yosemite Valley, Wawona, El Portal, and other areas, and adapted to lives with the newcomers in order to survive. By the time President Lincoln was presented with the Yosemite Grant in 1864, protecting vast stretches of land as part of “America’s Best Idea”, native people were once again living year-round in places like Yosemite Valley. In addition to their traditional practices, they also worked with and for their new neighbors, including providing services to early hotels. But it still wasn’t easy.

Although archaeologists have identified over 30 different historic villages in Yosemite Valley, by the early 1930s, they had been consolidated into one “old Indian village” that was located near the site where the medical clinic is now.

To make room for the hospital, the people were relocated to the “new Indian village” (Wahoga) just west of Camp 4, which was in place from 1931 to 1969.

Unfortunately, at that point, the housing policies changed, and the residents of Wahoga were once again asked to leave, just as their ancestors had been, and their cabins were removed from the site.

Fortunately, the Wahoga area has recently been set aside again for the preservation of Indian cultural heritage. Tribal elders have envisioned a sixty-foot Hangngi’ (traditional round house) and other structures built in the old ways as much as possible, and including a community building and cultural center. You can see them under construction now in Yosemite Valley.

Learn More

Learn more about Yosemite’s history at a local museum. (Photo: displays at the Yosemite Museum in Yosemite Valley)

For more information on Native History, be sure to stop in at a local museum. The exhibits and knowledgeable staff there can bring the cultural history of indigenous people to life.

The Sierra Mono Museum and Cultural Center is worth a side trip to North Fork (about an hour from Wawona). The center is dedicated to sharing a wide variety of artifacts that have been important for the Mono tribe’s cultural history, including the largest Mono Basket collection in the state, and over 100 animal exhibits.

The Yosemite Museum in Yosemite Valley is another delightful place to get information on the cultural history of indigenous people as well as other exhibits. Talk to the Indian Cultural Demonstrators who work there, and admire the beautiful basketry on display. Behind the museum, you’ll also find a reconstructed Indian village with examples of different kinds of structures, as well as information on some of the traditional uses of local plants.

The Smithsonian Institute calls The Mariposa Museum and History Center in downtown Mariposa, CA “The Best Little Museum of its Size West of the Mississippi”. There, among stories of the gold rush and pioneer history, you’ll also find an exhibit with native plants, mortar rocks, baskets, and photographs that tell the story of local Miwuk heritage and culture.